A Story for My Peeps--And a Sale for My E-books

December-r-r E-BOOK SALE

You might know about Smashwords. To be honest, I don’t know much. But one of my publishers, Draft2Digital, recently acquired Smashwords, so they are one entity. Smashwords invited all D2D authors to join their December e-book sale, so I did. From December 15 to December 30, 2022, (the kickoff to the real winter season in my home state of Michigan), all of my e-books, both Maggie Pill and Peg Herring titles, will be half off. Fifty percent. Basically, two for the price of one.

Is that cool (winter reference) or what?

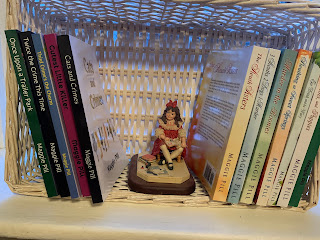

As a rule of thumb, Maggie Pill books are cozy mysteries, (e.g. the Sleuth Sisters & the Trailer Park Tales series) meaning they’re funny (I think), small-townish, and as non-violent as one can get when the story centers on murder.

Peg Herring books are all over the map, because I write the story that interests me at any given time. Those who’ve been with me through the years know that I started with historicals (the Simon & Elizabeth murders, the Dead Detective series), followed by a few stand-alone mysteries (Somebody Doesn’t Like Sarah Leigh, Her Ex G.I. PI), and several mystery series of three or four books each (The Kidnap Capers, the Loser Mysteries).

Lately, Peg’s books have turned toward what’s called women’s fiction (a term I don’t much like), the key being that they center on interesting women in intriguing situations. There’s always a mystery, but it isn’t the traditional whodunit kind where a single crime or criminal is the focus of the book.

If you’re interested, now’s the time, since they’re all half-price. Your best bet might be to wander through my websites and read up on the various offerings.

Maggie Pill’s site: https://maggiepill.maggiepillmysteries.com/

Peg Herring’s site: https://www.pegherring.com/

AND FREE (WHICH IS EVEN BETTER THAN HALF-PRICE)

It’s my holiday gift to all of you who buy my books, read my books, and sometimes write me little notes to say you enjoy my books. I’ve written a short story only for my friends and fans. Spoiler alert: It’s not exactly warm and fuzzy, but hey--I’m a mystery writer!

You’re Always Welcome at Our House

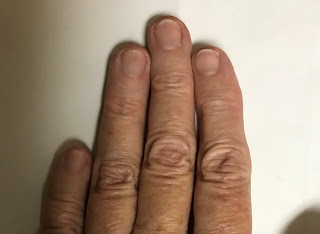

“You’ll have to do the digging,” Gram said as we stood over the body. “The way Arthur’s got my hands all knotted up, it’s hard to hold onto the shovel, much less make a hole.”

I nodded, aware that at eighty-three, Gram’s advancing arthritis made things she’d done easily in the past much more difficult. It wasn’t the least of her problems, but at the moment, it was a pretty big one.

“Once you get him in the ground, drive his car over to Shoepac Lake and get rid of it, like always.”

Shoepac Lake is a sinkhole, a pit almost a hundred feet deep that filled with water, unlike other sinkholes in the tip of Michigan’s mitten. The drop-off is close to vertical, so you can’t find the bottom more than a few feet from shore.

I knew what to do: drive the stranger’s SUV to a high spot on the lake’s north side, wind down all four windows, put a rock on the accelerator, and then knock the shift lever into drive with a stick. The car would shoot forward until its wheels lost traction and then it would drop straight down, into the pit. It was kind of creepy to watch, but kind of beautiful too. I wondered how many times Gram and I had stood in the moonlight, watching as water surrounded a vehicle, flooded its interior, and pulled it gently to the bottom.

Now I was supposed to do it all by myself. I voiced my disapproval in the only way I knew, with a complaint. “Two miles in the rain to get back here, on foot, in the dark.”

“You think I don’t know that?” Gram’s voice held a note of irritation I’d seldom heard when she spoke to me. With others, she was testy, but she’d always been gentle with her “Sweet Carla.”

“You’re fifteen now. Old enough to handle things when you’re told to.”

I regarded the corpse slumped over our kitchen table. He hadn’t been a particularly nice man, but a nagging voice told me he hadn’t deserved to die just because he was a problem for Gram and me. I knew if I said that aloud, Gram would repeat what she’d said before. “Sign out front says to keep out. Not our fault if they won’t do what they’re told.”

Gram and I had moved to the cabin twelve years before, shortly after Man first walked on the moon. Watching Neil Armstrong take that “giant leap for mankind” was my last clear memory of city life, television, and my mother. Before that day, I’d done normal things, like riding the bus downtown with Mom and going to the movie theater at the mall on my birthday. I vaguely remembered our apartment on the fourth floor of a shabby building with dim hallways and a variety of smells: fried potatoes, shawarma, frijoles, or curry, depending on the day and the direction I took. I’d had friends. I’d worn dresses and ribbons in my hair. I’d gone to school.

Gram lived across the hallway, and I’d stayed with her in the afternoons until Mom got home from work. Gram hadn’t been Gram then. She’d been Mindy, our grumpy neighbor, known for being willing to fight for what was hers. Even the punks in the building left Mindy alone.

She’d taken a liking to us for some reason, and when Mom’s boss switched her to afternoons and she needed somewhere for me to stay, Mindy had offered. Retired after twenty years as a pharmacy assistant, she wasn’t exactly kindly, but Mindy liked me, so I seldom saw her angry side. She was as strapped for cash as Mom and I were, counting her Social Security pennies while we got food stamps to augment Mom’s income as a waitress.

Then life changed. I was seven years old, though I remember that when people asked, I was more precise. I was seven and three quarters. Mindy had a TV, which we didn’t, and that afternoon she and I watched as a U.S. astronaut stepped onto the moon and into history. “Ain’t that something?” Mindy said, her voice low with awe. “Who’d ever think I’d see something like that in my lifetime?”

Mom didn’t come home at her usual time, but we didn’t worry. Mom picked up an extra shift whenever she could, but her boss frowned on the help using the business phone. If he hung around by the cash register, she often couldn’t call to let us know.

At eight-thirty, two policemen came to Mindy’s door. I remember they smiled, but their smiles weren’t happy ones. I heard phrases like traffic fatality and next of kin but didn’t understand them at the time. Gram was shocked and upset, moaning and repeating, “Oh, no. Oh, no.” When one of the officers mentioned foster care, Mindy jerked like she’d been poked with a pin.

“Kelly can stay here,” she told him. “She’ll need a friend, and we’re used to each other.” I didn’t understand the man’s reply, but it made Mindy’s mouth turn down even farther than usual. After a moment, she said, “I understand, but here’s the situation. I’m supposed to take little Kelly to an appointment with her allergist in the morning. What if I keep her here tonight, pack up her things in the morning, and take her to Social Services once she has the prescription refills she needs for her asthma?”

The cops probably shouldn’t have agreed to that, but they did. As they turned to go, repeating that they were sorry for our loss, I stood with my mouth open, unable to take in anything I’d heard. My mother was dead. I was completely alone in the world. I didn’t have asthma, and I’d never seen an allergist in my life.

As soon as the door closed on the men, Mindy turned to me. “Baby, your mama’s gone to Heaven. Do you want to stay with me or go and live with someone you never heard of before?”

The first part terrified me. The question that followed was easy. “With you.”

“All right, then. We’re going to have to leave.” Digging in a bowl of small items on a table by the door, she got out Mom’s spare key. “Let’s go pack you a bag.”

The next few days were a blur. Bits and pieces stick in my mind. I remember Mindy, on the morning after my mother’s death, called the social services office and told them I’d run away. In a querulous voice, she said I’d asked if I could call my dad in Toledo and tell him what had happened. “Of course, I allowed it,” she told the person at the other end of the phone line, “I thought to myself, ‘No harm in a phone call.’”

The social services lady was encouraged to imagine Mindy’s surprise when she found that little Kelly Beebe had disappeared in the night. “Her father must have come for her,” Mindy said as I stood right in front of her. “I don’t even know his name. Johnny Something, I think.”

At least she told the truth there. I didn’t know anything about my father either.

When she finished lying to the authorities, Mindy hauled boxes, bags, and suitcases down to the parking lot. She wouldn’t let me help, ordering me to stay inside and away from the windows. When she finished, we crept downstairs to the side entrance on tiptoe, like cat burglars. Checking to see that the parking lot was uninhabited at the moment, she hurried me outside. In a spot next to the garbage bin, Mindy’s old green Chevy sat, as it had since I’d known her, exposed to all kinds of weather. The roof had been scorched brown by the sun, the sides rusted from winter driving on Michigan’s salty roads. “Crawl into the back and scrunch down,” Mindy ordered, and she covered me with a blanket. “When we get out of the city, you can sit up front with me.”

Once I was out of sight, Mindy got into the driver’s seat, turned the key, pumped the accelerator, and muttered a few choice words. Her spell worked, and the engine fired. I felt the car back up, turn, and start forward. We stopped a lot and turned a few times. The blanket smelled of mothballs, but it wasn’t that bad. If I peeked around the edge, I could see a little bit of sky out the window and Mindy’s tight, gray curls up front. She talked the whole way, telling me how sad she was that Mom was gone but how we’d get through it together. I was sad too, and scared, but I trusted Mindy. Looking back on it, that wasn’t surprising. I had nobody else.

After about twenty minutes, Mindy stopped at a McDonald’s, where we had lunch. (I had no idea how long it would be until the next time.) Full of burgers and fries, we made our way to a town called Milford, where Mindy’s nephew lived. “Chester ain’t much good,” Mindy (who said I should call her “Gram” from now on) told me as she drove, “but he’ll help us out, long as he gets something out of it.”

Chester lived in a tiny house a few blocks off Milford’s Main Street. The lawn wasn’t mowed, and the porch looked like he’d just moved in and hadn’t yet found a place for all his stuff inside. Mindy said that wasn’t the case. “Chet collects stuff, mostly junk, crooked friends, and debt.”

From the start, Chester gave me a weird feeling, that sense kids have but can’t put into words. Skinny and small-built, he had little eyes and a big grin. When he saw me, the grin got bigger and his eyes got even narrower. “Come in, come in,” he invited, holding the battered wooden screen open for us. As I passed, he grabbed me and pulled me close. “You look like a girl that needs a rub,” he murmured in my ear. Holding me tight, he dragged his scratchy whiskers along the side of my face. It felt like a Brillo pad, only a lot creepier.

“Let her go,” Gram demanded. Chester did, but he laughed like he’d got away with something. I moved as far away from him as I could get, and for the rest of our time together, kept Gram between him and me.

We slept that night in Chester’s guest room, which was as full of junk as the rest of the place. We moved a dozen items off the bed, including a stuffed deer, a box that contained a set of balls for playing pool, and boxes marked, “Millie’s clothes.” They told me to go to sleep, but I didn’t, at least not until Gram came in. Instead, I listened while Chester and Gram plotted how to keep me out of the social services system. “Kelly and me need a place to live where nobody will think to look for us,” Gram said.

Chester thought about that. “What about Dad’s old cabin up on Dog Lake?”

Gram’s back was to me, but I saw her shoulders relax a little. “I forgot all about that place.”

“It ain’t a palace, but it’s on a dead-end road, and you can’t see it from the lake. Nobody’s likely to find you way out there.”

I learned later that Gram and her brother, Chester’s dad, had grown up in Onaway, a small town in northern Lower Michigan. Gram had moved to Detroit with her husband and remained there, even after he died from “too much booze and too many cigarettes.” The brother had also moved south, going to work in the auto industry. While their childhood home was sold when the parents died, Chester had held onto the family hunting camp, situated about halfway between Onaway and another small town called Atlanta.

“You said the cabin isn’t a palace. What kind of shape is it in?”

“There’s a guy who looks after it for me. Jim’s a pretty good handyman, and he don’t ask questions.” Chester gave Gram that greasy grin of his. “If my buddy shoots a deer in August, or if I park a motorcycle in the shed that I don’t exactly have the title to, Jim don’t say nothing to nobody.”

“What about living out there through the winter?” Gram asked. “I don’t want them finding Kelly and me frozen in our beds come March.”

Chester waved, dismissing her concerns. “You’ll have to do some winterizing, and it won’t be like living in the city, but you’ll do fine.”

“What if someone recognizes me?”

That brought a laugh. “You been gone, what—fifty years? Anybody that knew you back then is either dead or got cataracts. It ain’t like you’re gonna join the Friends of the Library, right?”

Gram considered. “I suppose we could do our business in Atlanta. No one there knows me.”

“Now you’re thinking smart,” Chester said approvingly. While I wasn’t old in years, I realized that to Gram’s nephew, smart meant “like a criminal.”

Next, Mindy—Gram—negotiated with Chester what he’d get paid for helping us. That was a long discussion, and I heard a few unkind words, but eventually, they reached an agreement. Gram came to bed then, and she murmured softly in my ear, “I think we’re gonna be okay, Sweetie Pie.”

At the bank the next morning, I waited in the car while Gram and Chester went inside and she added his name to her account. After that, she drove to the post office and changed her mailing address to Chester’s house in Milford. The deal was that each month when her social security check arrived in the mail, he would cash it and send two thirds of the money to a box Gram would rent at the post office in Atlanta. That two-thirds had been the hardest part of the negotiations, causing the most words I wasn’t supposed to hear. She’d offered twenty percent; he’d wanted half.

“It doesn’t leave us much to live on,” Gram had complained.

“What will you need?” Chester countered. “It ain’t like you’ll be going to cocktail parties or movie premieres.”

One of Chester’s crooked friends, Bobby-Jack, got us new IDs, a birth certificate for me and a driver’s license for Gram. With the birth certificate of a girl who’d died at birth, he explained, I could get everything else I needed when the time came: a driver’s license, a Social Security number, and even a passport. Gram frowned at the photo on the license she was given. “Doesn’t look much like me.”

“It’ll pass unless some cop gets suspicious,” he told her. “If you get stopped, be real sweet. You’re old, so they’ll probably let you off with a warning.”

Gram shrugged. “I guess beggars can’t be choosers.” Paying for our new selves took every bit of the cash my mom had kept hidden in a jar at the back of the refrigerator, but when Bobby-Jack left, we were no longer Miranda Gilbert and Kelly Beebe. Instead, we were Maria and Carla Butler.

Gram traded Chester her Chevy for his Dodge pickup. Her car wasn’t much in the looks department, but the truck was worse, having scrapes from what appeared to be metal poles on either side. “I think we’ll be okay, Sweetie Pie,” Gram said as she ground the Dodge’s floor shifter through the gears. “New names, different vehicle, and a place to stay that not many know about.”

“Will Chester come and visit us?” While I would never criticize Gram’s nephew, I dreaded the prospect of ever seeing him again.

She laughed. “Chet’s got zero interest in nature. Money will be tight, but I told old Chet that if he stiffs us on our share, I’ll drive down and peel off his useless hide with a dull knife.”

At the time, I never asked myself why Gram did all that to keep me with her. Later, I decided it was because my mother had been good to her. She had always listened to Mindy. She’d treated her with respect. And every few days, she’d sent me across the hall with homemade food: a plate of Swiss steak and potatoes, a bowl of soup, or a slice of her special chocolate cake.

Gratitude. It’s a noble emotion, so it might excuse things that aren’t so noble.

In the months that followed, when we had no one to talk to but each other, I learned that Gram had lost her only child, a five-year-old daughter, to a hit-and-run driver. Shortly afterward, her husband began the long and horrible battle with lung cancer that finally killed him. “I was convinced the world was a terrible place,” Gram told me once. “Then you and your mother moved in across the hall.” She shook her head slowly. “That woman was nothing but kindness and care.”

Gram had seen Mom and me as a spot of happiness in her life. When Mom died, it became me alone. That had been what led to us driving two hundred and fifty miles north, to a life neither of us was quite ready for.

Chet’s property was at the end of a two-track road that turned off a gravel road from another gravel road that exited a two-lane road that didn’t get much traffic. We found it late in the evening, after several false turns that led to a boat launch or a campground or nowhere. Bordered on all sides by state land, the camp wasn’t on the way to anywhere, so the chance of casual visitors was nil.

About twenty by thirty, the cabin was built of rough planks covered on the outside with shingles. The roof was tarpaper, but Gram pointed out, in an overly cheerful tone, that it had no tears or bad spots.

Inside, the main room was open to the rafters. “We’ll get us some rolled insulation and staple it up there,” she said, continuing the optimistic tone. “Lots of time to get it done before winter hits.”

A hand pump sat next to a sink in the corner that represented the kitchen. Next to it was a two-burner gas cookstove, and at ninety-degrees to that, a ‘50s-era refrigerator with round shoulders and a freezer the size of a shoebox. “There’s electricity,” Gram said quickly as I looked around, horrified. “They had to run the lines right by here to get to the state park, so Chet’s dad got himself hooked up.”

In the back corner was a bathroom with a toilet that flushed when you poured a bucket of water into it. The tiny shower operated by gravity, Gram explained. “We warm water on the stove, fill the tank, and set it on that overhead shelf.” I would soon learn that it was wise to wash quickly, lest the tank empty and leave me covered with soapsuds.

Centered on the cabin’s interior wall was a wood stove made by attaching a chimney pipe and metal legs to an old barrel. It was raised from the floor on a bed of bricks, and the wall behind it was covered with a special sheet of something meant to prevent it catching fire. Beside the stove was a wood box, empty in July, and a tin bucket filled with an assortment of sticks Gram said were for kindling a fire. She would teach me how.

Last was the bedroom, a dark space with an open storage rack and two beds made of planks and particle board, each covered with a ratty-looking mattress. “Beds first,” Gram said, but her tone hinted that her enthusiasm had lessened. “The rest we’ll worry about tomorrow.”

We dragged the mattresses outside and left them for the critters. Then we scrubbed the frames with cold water and rags until we were pretty sure the mouse turds were gone. In the open shelf unit was a pile of blankets, but one sniff made Gram reject them as well. “Luckily,” she said, “we have our own linens.” Opening a box she took from the truck, she dug out the blankets I’d had on my bed back in Detroit. My first night in the cabin wasn’t much like home, but the smell of my mom’s Breeze detergent and the ballerina bedspread she’d bought me for my seventh birthday helped.

The next morning we made toast on the stove, using a contraption Gram found in the cupboard. The triangular metal frame held two slices of bread, one on each side. “You set it over a burner and turn the flame down low, so it toasts one side at a time,” Gram said. “Pay attention, or you’ll get black toast to go with your cocoa.” I didn’t want that, so I watched the white bread turn golden brown and then turned the slices, achieving even browning on both sides. While I did that, Gram heated milk in a pan on the other burner. When it was almost boiling, she poured in a mixture of Hershey’s cocoa and sugar, making a delicious drink and a dip for the buttered toast.

Life at the cabin was hard, and for months, I was a pain in Gram’s neck. The big, empty outdoors scared me, and I groused that I hated living like Daniel Boone. I missed having friends to play with, and I didn’t understand why we couldn’t go anywhere. Aside from Jim, the almost silent handyman, we saw only each other. If we did go into town, I was ordered to avoid eye contact and answer yes or no, no more.

When I complained, Gram would remind me that if our real identities were discovered, I’d be taken away from her. I’d live with strangers, possibly adopted but more likely in a foster home or even a series of them. I admitted that the prospect of being under the control of strangers was worse than life at the cabin. Over time, I got used to the rhythm of life in the woods. The whisper of wind through the trees replaced the traffic sounds I’d been used to. The smell of pines was nicer than gas fumes. And while I wasn’t thrilled with the chores and the bugs and the loneliness, I was grateful for Gram, who loved and cared for me now that Mom was dead. “We’re alone in the world except for each other,” she’d say. “Nobody should come between us, Sweetie Pie. Nobody.”

As the leaves started turning, first a branch here and there, and gradually, a world of new colors, we prepared for our first winter up north. Silent Jim installed an electric pump, meaning the toilet flushed without buckets and water ran from the tap without wearing me out. “Next year we’ll get a hot water heater,” Gram promised, and that seemed like heaven.

We insulated everything that fall, walls, roof, and pipes. We stocked up on food, firewood, and tools Gram thought we’d need, like snow shovels and a blowtorch to use if the pipes froze despite the wrapping we’d done. She arranged for Silent Jim to plow the half mile between us and the road nearest road cleared by county trucks, so we could get out if we needed to.

Without realizing it, I had fallen in love with the Michigan woods. I explored different sections each day, making the acquaintance of birds, deer, raccoons, and elk. Sometimes Gram walked with me, but usually I went alone, and I soon knew my way around the forest better than she did. Winter was cold, but I found an old pair of skis in the shed. Snow made it easy to track animals, and I learned how each coped with the season, some making burrows, some building homes in hollow trees, and some bedding down in the swamps.

I missed going to school, but Gram was afraid of the questions they’d ask if she enrolled me in classes. “‘Where are her records?’ will be the first thing,” she said, “and we haven’t got any. We’ll have to get you educated other ways.”

That meant home-schooling, so Maria and Carla Butler became well-known in the local library system. The name was common enough in the area that people hardly paid attention to a couple more Butlers, assuming we were cousins attached to the family somewhere along the line. Long winter nights were spent reading and discussing. Why had the Indians helped the colonists? How does water freeze? What might green eggs and ham taste like?

The first person who threatened our new life came along by accident. It was April of 1970, the year after we came to the cabin. The winter had been long, but a day came when, although dirty piles of snow still pock-marked the woods and lined the roads, the air warmed to t-shirt weather. Mother Nature seemed to whisper, “We’re done with winter now.”

I was sitting outside, on an old Adirondack chair I’d found upside down in the shed. Gram was mopping floors, so I’d set the radio in the window, facing out, so I could listen to music while I soaked up the sun’s warmth. Between songs, the DJ announced that the Beatles were officially disbanding. He played “Here Comes the Sun” as a tribute to them and to the warm day.

I must have dozed off. When a car pulled up beside me, I opened my eyes and saw the DNR emblem on its door. Shutting down the engine, the driver got out of the car. He was tall and very blond, and a frown seemed a permanent part of his face. I was scared, but there was no way I could avoid him at that point, so I stood and tried to smile as I waited for him to speak. His first words came in a growl. “Who’re you?”

“Carla,” I replied.

“You living here?”

“For a while.” In small towns, everyone is curious about strangers, so Gram and I had sometimes been asked, Where are you from? What brought you here? The inquiries were meant to be friendly, but we were always careful how we answered.

This man wasn’t the friendly kind of curious. In fact, he brought to mind bullies I’d seen at school, kids who were looking for somebody to push around. Glancing at the cabin and the yard, he said, “This isn’t residential property.” While I didn’t understand the term, it sounded like a challenge.

The door opened with a creak and a scrape, and Gram came outside, wearing corduroy jeans and a flannel shirt. She carried a mop, and she set the handle down on the porch, holding it like a flag of ownership. “Hello, Officer. Can I help with something?”

“Maybe.” His tone didn’t get any friendlier. “I’m going to need you to prove you’ve got the right to live here.”

“Has someone reported us for some reason??”

“No,” he admitted. “I was checking the back roads and saw the smoke from your chimney. Not many hunters up here this time of year, so I thought I’d better take a look.”

“You patrol all alone? Isn’t that dangerous?”

He shrugged. “I can handle myself.”

“That’s good.” Though her tone remained pleasant, Gram watched the man closely. I saw what she called “brain-wheels” turning in her head, though I didn’t know what they were churning out.

The man strutted up the porch steps and stopped, looking down at Gram. “Let’s start with your identification. When I get back to the office, I intend to call the owner of this property and see if he knows he’s got a couple of squatters. Somebody—either you or him—has some explaining to do to the state of Michigan.”

My heart sank. Even though my experience with Gram’s nephew had been brief, I couldn’t imagine Chester supporting our cause if someone in authority started asking questions.

Gram took a while to respond, but then she stepped toward the open doorway. “Please, come inside. I’ve got coffee on the stove, and you can have a cup while I dig out the information you need.”

He followed Gram inside. I came after, like a forgotten kitten. He had to duck to get through the doorway, and he stopped just beyond it, causing me to almost run into his backside. “Nice place.”

The muscles in Gram’s face tightened at his tone. I’d grown used to the tattered furniture, the rough floorboards, and the ancient appliances, but the man’s disgust was evident.

“Please, sit,” she said. “I’ll just warm the pot a little.”

The officer dragged one of our two chairs away from the table and examined the seat for dirt before he sat. I didn’t like that. He might not approve of the condition of our things, but they were as clean as anyone’s.

Gram stood at the sink, fiddling with the cups. “What do you know about this property?”

“Plat book says it’s owned by Chester Marshall.”

“Chester is my nephew.” Gram poured two cups of coffee and set one before him. “When our home in Alpena burned down, he said my granddaughter and I could live here until I find something for us.”

“Well, that’s real nice of him, but you can’t live on recreational land for more than 120 days at a time.”

“Oh.”

Taking a drink of coffee, he said, “Yeah. Oh.” The sneer in his voice made me shudder.

“I guess we’ll have to look into that.”

“Oh, we will.” He took another drink.

“I have to say, Officer—”

“Palmer.”

“Officer Palmer, I’m surprised by your attitude. Carla and I aren’t bothering anyone and we’ve given you no reason to be so…disagreeable.”

“Maybe I don’t like people that think they can do whatever they want.” Another drink, and then he added, “This state’s got laws.”

“Does it.” Gram’s eyes never left his face.

Palmer opened his mouth to say something, but suddenly his face turned an odd color. His whole body spasmed, and a few seconds later, he lay dead on the plank floor.

I remember feeling like my chest might explode. “What’s wrong with him, Gram?”

“He’s dead, Sweetie.”

“What happened to him?”

“I guess we’ll never know for sure. But we can’t let anyone find him at our place, or they’re bound to ask questions.” She glanced out the window at the dark green pickup. “I’ll move his truck so it’s out of sight, and then I’ll have to think for a while. You stay here.” I made a sound of objection, unnerved at being left inside with a dead man, but she ordered, “Go into the bedroom, close the door, and stay there until I call for you.”

Though I obeyed, I watched what Gram did, moving back and forth from the room’s single, tiny window to a spot where a warped board in the bedroom door allowed a slit of view into the main room. First, she got a shovel from the shed and dug a hole in the yard. That took her a long time, because she had to stop and rest every few minutes. When the depth suited her, she rolled the body onto a blanket and hauled it outside, maneuvering backward out the door and across the sandy ground.

The DNR truck was the first vehicle we dropped into Shoepac Lake in the middle of the night, but that didn’t happen right away. It took Gram a while to come up with the idea of using the sinkhole as a disposal site, and then we had to wait a few more days for the roads to dry out, so she was sure she could get it there without getting stuck.

We lived in fear for months. I wasn’t even sure what I was afraid of, but I sensed that danger dogged our footsteps. Each time we went into town, Gram bought the local paper and combed it for information on the missing officer. “Things turned out good for us,” she told me. “Palmer didn’t tell anyone exactly where he was going that day.”

My reading skills were building nicely, so I read the newspapers too. Palmer’s intention had been to patrol the area to see how the deer herd had fared through the winter. When he didn’t return to work, a search was launched, but his territory as a DNR officer covered acres and acres of land populated mostly by trees and wild animals.

When no sign of Palmer or his truck was found, his soon-to-be-ex-wife offered an explanation that was a life-saver for Gram and me. He’d left the state, the former Mrs. Palmer claimed, to avoid paying child support for his three young children. Since Palmer had by all accounts been a complete jerk, it was a story most people could accept.

The second time Gram did away with someone came a few years later, in 1974. I was twelve, it was August, and President Nixon had resigned, being in a bunch of trouble. On an afternoon that was too hot to do much of anything, we lolled on the porch, sipping iced tea and sweating. A pickup came down the road, slowed, and then turned in at the cabin gate. The driver was a logger who told us he had a contract to cut timber on some of the state land in the area. “As long as I’m gonna have my trucks out here,” he told Gram, “I’d like to take those big old white pines. I saw them from the other side of the lake.”

We all turned to look at the trees, which blocked view of our cabin from the lake and provided a charming backdrop for it from the road. Gram and I saw old friends, but the logger saw dollar signs. When Gram said she wasn’t willing to sell the trees, the man, who said his name was Ed Dargan, was clearly unhappy. “I think I’ll talk directly to the landowner,” he said. “Clerk’s office says that’s Chester Marshall, down in Milford.” With a curl of his lip, he added, “Lots of times, a woman don’t know a good offer when she gets one.”

“Don’t I.” It wasn’t a question, and I saw Gram’s brain-wheels turning again.

“We wouldn’t be any bother to you ladies. My crew would be in and out in two days, three at the most.”

“Your crew knows about our pine trees?”

He frowned. “Well, not yet. I’m the boss. I do the scouting.”

“So they don’t know you’re out here looking at these trees right now.”

His laugh revealed contempt for her lack of understanding. “When it’s time, I tell my guys where to cut, and they do it.”

Gram thought for a few seconds. “Come inside. Mr. Dargan. I’ll fix you a glass of iced tea, and you can explain this financial opportunity you’ve offered so I can understand it.”

Pleased that she might reconsider, Dargan came inside. While Gram set out cookies and poured him a glass of tea, he bragged about what a great businessman he was. Behind his back, Gram took a small tin cannister from the cupboard and added a teaspoon of powder to the glass of tea she then offered him. “So nobody keeps track of where you are all day, Mr. Dargan? That seems a little dangerous.”

He waved away her concern. “I’ve been all over the county today,” he said. “I just drive until I see a likely stand, and then I talk to the people and make a deal.”

Mr. Dargan never made a deal that day.

Being older then and a little wiser, I guessed Gram had something to do with the man’s death. It was wrong, and it bothered me. “What happened to him?”

She replied without looking directly at me. “I suppose he had a bad heart, Sweetie Pie. He’s been tromping all over the place all day, and it just caught up with him. I have to do what I did before, so you go into the bedroom and wait until I’m finished.”

How do you accuse the only person in the world who cares for you of being a criminal? How do you ask her to please, pretty please, stop being a murderer?

In the end, I had to help. The guy was “hefty,” Gram’s term, and she couldn’t get him over the raised threshold. “Sweetie, you’re going to have to come and help me,” she called.

Rigid with dread, I held the man’s feet and lifted until Gram got his oversized butt through the doorway. “All right, you’re done,” she said. I scurried back into the bedroom, where I watched her bury our second unwanted guest in a hole about twenty feet away from the first. Again she had to stop frequently and rest, and as horrified as I was at what she’d done, I also felt like Miss Lazybones for not helping.

But it was a grave. That was wrong.

Several times, Gram had warned me to leave the tin canister at the back of the cabinet untouched. “It’s for getting rid of mice,” she said, but after Mr. Dargan, I suspected the tin contained more than rodent poison. Gram’s years as a pharmacy assistant explained how she knew about killing people, though it didn’t help me understand how she could do it. She claimed the powder tasted sweet, like sugar, and it acted quickly. Neither the DNR guy nor the timberman had managed to do anything except tip over. No groan of pain. Not even a “What…?” I didn’t think they knew what hit them.

The third death convinced me that I shared the cabin with a killer. It was Feb 11, I was thirteen, and Margaret Thatcher had recently become Prime Minister of England. I was thrilled to think that two women would run a whole kingdom, Thatcher doing the business part, and Queen Elizabeth representing the monarchy. Women in power. Cool.

We had a midwinter thaw that made the roads slick in some places and mushy in others. Huge puddles that were tricky to navigate around formed on the edges. Despite the conditions, a woman named Denise Penske arrived in our yard in a Chevy Bel Air that was almost as long as our house. About fifty, with dyed-red hair and Petoskey stone rings on six of her ten fingers, Ms. Penske was all gush and optimism. “This place is charming,” she said as she got out of the car. “I mean the trees and the…it’s just charming!” Grabbing Gram’s arm, she said, “We have to talk.”

Clearly unwilling but resigned, Gram ushered Denise inside, where we listened to her spiel. She’d been all over the area looking at vacation-home possibilities, she told us in her breathy, childish voice. Her specialty was hand-selecting properties for down-staters looking to buy an up-north summer cottage or weekend cabin. She’d had a customer on the hunt last fall, and she was sure she could get us a “very nice” price for our “charming bit of up-north heaven.”

When Gram said no in a tone I recognized as final, Denise wasn’t deterred in the least. “They’re from Saginaw,” she said. “They’ve been renting on Black Lake every year, but now they want to buy. They want a place that’s kind of secluded, more private that those shoulder-to-shoulder places on the big lakes.” She gave our home a critical glance. “They’ll probably level this and build a nice two-bedroom closer to Dog Lake.” With a never-mind-the-details wave of her hand, Denise continued, “Anyway, they’re hoping to choose a property during their kids’ Easter break next month. Then they can start work on it in June, as soon as school is out.” She regarded Gram speculatively. “That would give you several months to find a place in town. If you don’t mind me saying so, you’re too old to be living this far from a hospital, or a main road, for that matter.”

Rising, Gram set the kettle on the stove. “Cup of tea?”

“Why yes, I’d love one.”

“Are you a married woman, Ms. Penske?”

“Divorced. No kids.” She gave me her professional smile. “Though if I could have had a daughter as pretty as this one, I might have considered it.”

“Carla is a treasure,” Gram said with her back to us.

I smiled nervously at the Realtor. “You probably should go, or you’ll be out in the woods past dark.”

Lost in her plans, Denise ignored me completely. “As soon as the Jacksons arrive, I’ll bring them out here. You’ll see for yourself what great people they are, and then we can sit down together and talk about a sale.”

“If she’d taken no for an answer, she’d have been okay,” Gram said later as we walked home from Shoepac Lake. Sensing my unhappiness, she added, “In a few more years, Sweetie Pie, you’ll be a legal adult. Until then, we can’t let people poke into who we are and why we’re here.”

They came looking for Denise. When a sheriff’s deputy knocked at the door, Gram greeted him with a smile. She explained that we were living there temporarily because our house in Cheboygan had burned. He listened politely but didn’t seem to care. He was focused on the missing woman, who was a pillar of the local community and president of the Chamber of Commerce.

Gram admitted the Realtor had visited, though she wasn’t sure when. She turned to me, asking if it had been three days ago or four. I stayed silent, but Gram didn’t seem to notice. To the deputy, she said, “She was looking for properties to represent, but we didn’t know of any. Has she had an accident?”

“She’s missing, ma’am.”

“Missing!” Gram frowned and shook her head. “Oh, my. The search will be difficult now that winter has come back with a vengeance. I’ll pray for her, and for you all as you try to figure out where she might have gone.”

As I got older, Gram decided I needed to see the world a little. We visited local towns, like Mackinaw City, Alpena, and Gaylord, so I could soak up the history and culture of the area. We toured the Besser Museum, Call of the Wild, Fort Michilimackinac, and other attractions. Once we went all the way to Traverse City, because I was dying to see a live play. We had dinner in a really nice restaurant called Big Boy, and then we went to see the show. For two-and-a-half hours, I sat mesmerized by the music, the costumes, the colors, the whole experience.

The downside of the trip was Gram’s driving. After years in the woods, the busy roads and city traffic made her nervous. She kept running off the pavement, because she said it felt like oncoming cars were over the centerline. And in Traverse City, I had to holler twice when she almost hit people who were crossing the street in front of us.

When the play was over, Gram suggested that I should drive home. “I’ll be even worse now that it’s night,” she told me. “All the lights look fuzzy and kind of wavery.”

I’d taken the pickup out on our road quite a few times, practicing, so I had the feel of driving. I knew the rules of the road too, having studied the driver’s license booklet, in case Gram ever let me take the test and get my license.

I did okay. I was a little scared until we got out of the city, but after that, I simply followed the road signs until we were in familiar territory again.

At the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal, Nadia Comaneci won three gold medals in gymnastics. Gram had been sick all spring, and even once summer arrived, she coughed a lot and had trouble getting her breath.

That summer, two backpackers came by the cabin. They might have gone on their way without harm, except the woman recognized Gram. “Aren’t you Miranda?”

“No,” Gram said quickly. “My name is Maria.”

“She does look like Miranda,” the husband said. “And I remember she said she grew up around here.”

“We worked together at the Walgreens on Day Street in Detroit,” the wife said. “And sometimes we played cards with you and Greg. Don’t you remember?”

“You’re mistaken.” Gram’s lips were tight. “I’ve always lived in northern Michigan.”

The man smiled slyly. “You wouldn’t try to kid us, would you?”

“It wasn’t me.”

They fell into a sort of double pout. Shifting his backpack, the man said to his wife, “The lady’s got a secret, Blanche. I guess we should drop it.” After a second, he added, “Even though you’ve got the same chicken pox scar on your forehead that Miranda had.”

At that point, Gram stood up, coughed once, and invited, “Come inside and have coffee with us.”

I had to dig the graves that time, and I remember being both angry and sad. Gram watched, and all she said was, “A bigger grave, but at least there’s no car to dispose of.”

“Gram, you can’t keep killing people just because you want to,” I said, stabbing the shovel into the sandy ground. “Those people weren’t mean or anything.”

“But you saw their faces,” she responded. “They knew I was lying. They wouldn’t have given up.”

Again there was a search, but the exact route the couple had taken was unknown. With miles and miles of hiking trails in the area, the authorities weren’t optimistic about their chances of being found.

In November, shortly after my fifteenth birthday, everything changed. Gram had been sick again, and while she insisted it wasn’t serious, I suspected it was. As she lay listlessly on her bed, I listened to reports that nine hundred people had died at the command of a madman named Jim Jones. Gram hardly reacted when I recounted the tragedy at the People’s Temple. It hurt her to move around most days, so I did all the work while she slept in the dark bedroom. Once in a while she’d have a good day, and she’d get up and sit at the table. I fed her soup and offered aspirin, our go-to medicine. Since she wouldn’t even discuss seeing a doctor, that was all I could do for her.

When the knock came, I jumped in surprise. I hadn’t heard the car pull in or steps on the porch, which shows how worried I was about Gram. She’d been a little better that morning, managing to make her way to an old rocker that sat next to the wood stove.

Opening the door, I found a woman with her hand raised, about to knock a second time. “Oh,” she said, taking a step back. “Hello.”

“Hi.” Glancing past her, I saw the car she’d arrived in. She was alone. “Can I help you?”

“I’m from the school,” the woman said. “I’m the new guidance counselor, Gina Tibbets.”

“Oh.”

We each waited for the other to speak again. Ms. Tibbets probably expected to be invited inside. I expected her to tell me what had brought her to our home.

“You’re Carla, right? Could I come in for a few minutes?”

I looked to Gram, who raised her brows in a what-can-you-do? manner. I backed away so our visitor could enter. “Sure.”

Ms. Tibbets glanced around, taking the measure of our place, but she didn’t seem put off by our mix-and-match cookware and second-hand, Salvation Army chairs. To Gram, she said, “You must be Mrs. Butler. I just recently learned that the two of you live out here, and I thought I might offer you some help.” She turned back to me. “You’re home-schooled?”

“Yes.”

She smiled, letting me know she had nothing against that. “I wondered if you and your grandmother are aware that the school can provide services to round out your education. You could take music or art classes during school hours, or you might join extracurricular activities, like drama club.”

Drama. Ever since we’d gone to see The Sound of Music in Traverse City, I’d dreamed of stepping onto a stage. I’d wondered what it would be like to have an audience listen to my every word, watch me dance, hear me sing. How would it feel when they clapped and clapped in appreciation of my performance?

“She’s not interested.” Gram’s voice came from behind me.

“Oh.” Ms. Tibbets looked from me to Gram. “There are other possibilities. She could join the science club or participate in sports or weight training.”

“Carla gets plenty of exercise right here,” Gram said. “And I’d bet she knows more about literature and history than most of your students do. While she doesn’t like math much, she’d still outdo half of them.”

“Ms. Butler, I’m sure you recognize that being part of a school group does more than teach a young person a given subject. Carla could benefit from associating with kids her own age.”

“I think that’s up to Carla and me to decide.” Gram’s face was like a thundercloud.

“Of course it is.” Ms. Tibbets seemed at a loss for a moment, but then she tried again. “Technology is taking off, and I doubt that any of us can imagine what the world will be like in a few years. Shouldn’t Carla know about things outside this property and this lifestyle?”

“She doesn’t need to.”

I saw the effort it took for the teacher to keep from arguing with Gram. “Maybe you should ask Carla what she’d like to do.”

Gram considered for a moment and then asked, “Who sent you out here, Ms. Tibbets?”

“No one.” She spoke to me, though she glanced at Gram from time to time. “I saw the two of you at the library in town one day, and since I hadn’t seen you at school, I asked the librarian who you were. She said she thought you lived somewhere near the state park, so I dug around some more and put bits and pieces together until I had a vague idea of how to find this place.” She shuffled her feet a little on the wood floor, and I sensed that this visit—her desire to give me choices about my future—really mattered to her. “Today I was on my way home from a conference, and I saw the sign pointing to the state park.” She smiled. “It was an impulse, but I thought, “Why don’t I find that girl and offer her the chance to expand her horizons a bit?”

“I hope your visit won’t make you late getting home to your husband.” Gram’s voice was odd, and I turned to look at her. The brain-wheels were turning.

“Oh, I don’t have one,” Ms. Tibbets said with a shy smile. “Not yet, anyway.”

There was a brief silence before Gram said, “Can I fix you a cup of tea?”

I spoke quickly. “She needs to get home, Gram.”

“It’s just a cup of tea, Carla.” Gram’s glance was a warning. “How long can it take?”

“That would be nice,” Ms. Tibbets said. She gave me a look that revealed what she was thinking. With more time, she could convince Gram to go along with her ideas.

“Sit down, then,” Gram said, rising from the chair with painful slowness. “It’ll just be a minute.”

I sat opposite our guest, one eye on her and the other on Gram. As Ms. Tibbets described the production schedule for the drama club that year, Gram shuffled to the stove and put water on to boil. She had to lean on the sink as she moved to the cabinet and took out the tin cannister. Her hands shook as she added a spoonful to one of the cups.

“I’m the drama director,” Ms. Tibbets was saying. “We did Meet Me in St. Louis last weekend, and I’m already making plans for The Wizard of Oz next spring.”

“I loved that movie.”

“You’d make a great Dorothy, although you might want to start with a less difficult role. The person who plays her has a lot to memorize.”

“I wouldn’t mind,” I said. “I memorize poems all the time, just because I like to.”

“Here you go,” Gram said, setting a mug of tea in front of Ms. Tibbets.

“Here, Gram,” I said, rising from our only other dinette chair. “You sit here.”

“Thanks, Sweetie Pie.” Leaning heavily on the back, Gram moved into position and dropped rather than sat in the chair. Her face pinched with effort, and I thought about her growing list of ailments. Arthritis. Fading vision. A hip that often failed to hold her upright. Stomach pain that doubled her over sometimes.

I looked at Ms. Tibbets, who, though I didn’t know it then, would become my champion, my foster mom, and my mentor. She would encourage me to formalize my studies and eventually become a teacher myself.

All I saw that day was a woman I instinctively liked, one who’d done nothing more than try to be kind.

“Look!” I said, pointing toward the window. “It’s snowing.”

When they turned away, I switched Gram’s cup with our guest’s.

Comments

Post a Comment